D.P. Walker

Some memories of Gerard Reve

I first met Gerard thirty years ago. An old friend of mine, Angus Wilson (now Sir Angus), had lent him his flat in London, and suggested that I should get in touch with him. The date is fixed in my mind, because Gerard, having learnt my age, which was thirty-nine, asked me whether I was worried by having so soon to pass that definitive frontier between youth and middle-age: forty years. Fortunately, I was not, and could therefore say so with convincing sincerity. The question was undoubtedly meant to upset me a little, and, had I given any signs of distress, would have been followed up by remarks about a few grey hairs, an incipient double chin, and so forth.

This was my first encounter with a characteristic of Gerard’s that he has still not lost: the compulsive need to give friends little jabs. I am still puzzled and unsure about the motives and origins of this behaviour. I will suggest a few explanations, all of which may be true.

One might suppose that the main motive is to gain attention; as a small child will do something naughty or be rude to a grown-up, because it wishes at all costs to be noticed. But this is improbable, both because Gerard can usually make himself the centre of attention without effort, and because the jabs occur also when he is alone with you and has your undivided attention. A more likely comparison is with the mock-fights carried on by kittens and puppies: rather rough games, with sado-masochistic undertones. This explanation is borne out by the facts that, if one replies to a jab by striking back, Gerard takes this with great good humour, and that he has strong sadistic desires. (I shall always be profoundly grateful to him for his frankness about these, which gave me the comfort of realizing that I was not alone in having such sexual inclinations.)

But the jabbing business is not merely a game; one has the feeling of being put through a test: if you can bear the jab without flinching, or if you hit back, you have passed the test. If this is so, then the above question about my age was a test designed to resolve the following doubt: is this obviously middle-aged, but still quite handsome man, stupidly vain about his good-looks and wretchedly afraid of losing them, or is it just possible that he is unaware of being attractive? Let’s try a jab. If he’s upset I might enjoy torturing him a bit; if he’s not, he might be worth knowing. If he hits back, we can have a nice little mock-battle, with a few real hard blows.

Finally, I would suggest that this behaviour springs from the wish to épater le bourgeois – ideally, the whole of the Dutch, liberal, left-wing bourgeoisie, but, better than nothing, to shock one mild, humanitarian English bourgeois such as myself. This is certainly an important underlying motive that accounts for much of Gerard’s behaviour and expressed opinions, both private and public, and it makes it very difficult to distinguish the genuine individual from the deliberately shocking persona displayed. I am still not sure whether he really likes cheap and hideous artificial flowers, or really enjoys eating boiled heart and brussel-sprouts (a recipe given him by an old blind basket-maker in Provence); and moreover, which is far more important and truly worrying, I do not know whether he really thinks that negros are an inferior race, or to what extent his conversion to Roman Catholicism was due to the wish to outrage conventional liberal opinion. As for the former, I don’t think he is stupid enough to be a racist, though he is silly enough to believe in astrology; as for the latter, I know that he is deeply and seriously concerned about religious matters. At any rate, in spite of these doubts I remain convinced that he is not a truly wicked, stupid or cruel person, and I know by experience that he is a good friend and a delightful companion.

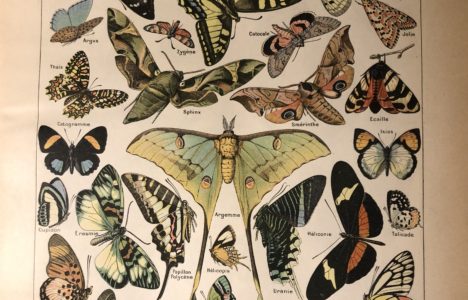

It is perhaps silly and naïf to hope to distinguish his genuine personality and opinions from what he displays. He sees everything through such a shimmering, multicoloured mist of sexual fantasy that he could not, I am sure, make the distinction himself, if he tried. This strange vision of the world is one factor in his success as a writer; a more important factor is his capacity for hard and detailed work. But what makes him more than a

merely brilliant writer in the black romantic tradition, and what makes him a sane and decent human being, is his sense of humour.

A good sense of humour is, I think, a life-line to reality, if it includes, as it should, the ability to laugh at oneself as well as at other people. This is what saves him from being completely crazy and destructive as a private person, and, as concerns his writing, what provides the salt and bitterness in what would otherwise be an over-rich, too highly spiced and heavy pudding of sex and religion. (By a good sense of humour, I mean of course one that is like my own.)

As one would expect, Gerard’s humour often takes bizarre and esoteric forms. Soon after I first met him, I received a post-card announcing that he would come to lunch on the next day and that, after we had eaten, we were to go into the park ‘a.w.th.b.’. These mysterious letters, over which I puzzled in vain, turned out to mean: ‘and watch the boys’, which indeed we did. I later imitated this device in the foreword to my book on hell, in which I thanked him for help in translating some 17th century Dutch texts, referring to him as: ‘Gerard Van Het Reve modb’. Neither the publishers, nor any of the few readers of the book, suspected that these initials referred to anything but some title of honour; but in fact they mean: ‘My own darling boy’. I have just discovered that P.G. Wodehouse, when writing in the character of Bertie Wooster, employs the same simple but effective device, for example (from Righto Jeeves), after an example of particularly atrocious female malice and treachery, ‘as that wise old bird Kipling remarks, the f. of the s. is more d. than the m.’.

At that time I lived in a tumble-down old flat near Notting Hill Gate, quite near Hyde Park, which was where we w.th.b. Gerard would quite often ring my bell, and in winter time say, as he hurried upstairs, ‘Poor Gerard is a-cold’. Then, as he crouched over the gas-fire, I would offer him something to eat and drink, which he always eagerly accepted and consumed, voraciously and with astonishing speed. Then, however frugal the meal, it was followed by a traditional formula of thanks: ‘Well, the Queen may have had a more expensive meal, but she certainly hasn’t had a more delicious one’.

To revert for a moment to the jabbing-friends business before I end this

brief note: whatever the motive behind it, I am quite sure it has nothing to do with envy, for the following reason. Writing is the mainspring of Gerard’s existence, and I, in a very different way and at a lower level, am also a writer. Now Gerard has not only, unlike most of my friends, bothered to read my books, but has been most generous in expressing his appreciation of them, an encouragement for which I am deeply grateful.

My later memories of him are mostly very happy ones of holidays spent at his house in Friesland, and more recently in France; he is a wonderfully kind and considerate host, though there is still the occasional jab – but these have become less frequent, and I have learnt over the years to bear them without wincing. I hope to have many more such happy, carefree times with him before we both go to our long rest.