Ik had de afgelopen week een paar interessante dingen gelezen die ik met jullie wilde delen, en al weet ik nog niet precies wat ik er over wil zeggen (om mezelf vast in te dekken voor wat ik later in dit stukje schrijf: ik denk er wel degelijk hard over na), het is leuk als jullie meedenken, dus

-Hier is bijvoorbeeld het einde van het essay Fictional Futures and the Conspicuously Young (1987) van David Foster Wallace, waarin hij ageert tegen oa het nihilisme in de dan huidige literatuur. Het is zo boos en ook grappig en waar, ik werd er vrolijk van!*/**

…Exciting is also confusing, and I’d be distrustful of any C.Y. (Conspicuously Young [writer]) snot who claimed to know where literary fiction will go during this generation’s working lifetime. (…) We seem, now, to see our literary innocence taken from us without anything substantial to replace it. An age between. There’s a marvelously apposite Heidegger quotation here, but I’ll spare you.

The bold conclusion here, then, is that the concatenated New Generation with whom the critics are currently playing coy mistress is united by confusion, if nothing else. And this might be why so much of the worst C.Y. fiction fits so neatly into the Three Camps reviewers consign it to: Workshop Hermeticism because in confusing times caution seems prudent; Catatonia because in confusing times the bare minimal seems easy; Yuppie Nihilism because the mass culture the Yuppie inhabits and instantiates is itself at best empty and at worst evil—and in confusing times the revelation of some- thing even this obvious is, up to a point, valuable.

Well, but it’s fair to ask how valuable. Of course it’s true that an unprecedented number of young Americans have big disposable incomes, fine tastes, nice things, competent accountants, access to exotic intoxicants, attractive sex partners, and are still deeply unhappy. All right. Some good fiction has held up a mercilessly powder-smeared mirror to the obvious. What troubles me about the fact that the Gold-Card-fear-and- trembling fiction just keeps coming is that, if the upheavals in popular, academic and intellectual life have left people with any long-cherished conviction intact, it seems as if it should be an abiding faith that the conscientious, talented, and lucky artist of any age retains the power to effect change. And if Marx (sorry—last dropped name) derided the intellectuals of his day for merely interpreting the world when the real imperative was to change it, the derision seems even more apt today when we notice that many of our best- known C.Y. writers seem content merely to have reduced interpretation to whining. And what’s frustrating for me about the whiners is that precisely the state of general affairs that explains a nihilistic artistic outlook makes it imperative that art not be nihilistic. I can think of no better argument for giving Mimesis-For-Mimesis’-Sake the chair than the fact that, for a young fiction writer, inclined by disposition and vocation to pay some extra attention to the way life gets lived around him, 1987’s America is not a nice place to be. The last cohesive literary generation came to consciousness during the comparatively black-and-white era of Vietnam. We, though, are Watergate’s children, television’s audience, Reagan’s draft-pool, and everyone’s market. We’ve reached our majority in a truly bizarre period in which “Wrong is right,” “Greed is good,” and “It’s better to look good than to feel good”—and when the poor old issue of trying to be good no longer even merits a straight face. It seems like one big echo of Mayer the fifties’ ad-man: “In a world where private gratification seems the supreme value, all cats are grey.”

Except art, is the thing. Serious, real, conscientious, aware, ambitious art is not a grey thing. It has never been a grey thing and it is not a grey thing now. This is why fiction in a grey time may not be grey. And why the titles of all but one or two of the best works of Neiman-Marcus Nihilism are going to induce aphasia quite soon in literate persons who read narrative art for what makes it real.

And, besides an unfair acquaintance with many young writers who are not yet Conspicuous and so not known to you, this is why I’d be willing to bet anything at least a couple and maybe a bunch of the Whole New Generation are going to make art, maybe make great art, maybe even make great art change. One thing about the Young you can trust in 1987: if we’re willing to devote our lives to something, you can rest assured we get off on it. And nothing has changed about why writers who don’t do it for the money write: it’s art, and art is meaning, and meaning is power: power to color cats, to order chaos, to transform void into floor and debt into treasure. The best “Voices of a Generation” surely know this already; more, they let it inform them. It’s quite possible that none of the best are yet among the Conspicuous. A couple might even be . . . autodidacts. But, especially now, none of them need worry. If fashion, flux and academy make for thin milk, at least that means the good stuff can’t help but rise. I’d get ready.

Misschien is dit een pleidooi voor engagement, dat vind ik lastig te zeggen, maar over engagement wilde ik het niet per se hebben (daar hebben Shira Keller en Marko van der Wal eerder deze week al interessante dingen over geschreven). Wat mij in dit stuk vooral aanspreekt is de mate waarin Foster Wallace roept om literatuur die geen uiting van leegheid is (waarbij leegheid dus niet per se het tegenovergestelde van engagement is; eerder lijkt hij zich uit te spreken tegen leeg engagement – goed voorbeeld is wederom het twitter account van Abdelkader Benali dat Shira Keller zo terecht onderuit haalt). Als ik de hier toepasselijke Heidegger-quote zou kunnen kiezen zou het er eentje zijn waarin Heidegger schrijft over wat hij Gerede noemt; geklets of ‘idle talk’. Idle talk is een vorm van praten die niet echt ergens over gaat, omdat de woorden door degene die ze uitspreekt niet langer begrepen worden; deze persoon kent ze alleen ‘van horen zeggen’: “The groundlessness of idle talk is no obstacle to its becoming public; instead it encourages this. Idle talk is the possibility of understanding everything without previously making the thing one’s own. If this were done, idle talk would founder; and it already guards against such danger. Idle talk is something which anyone can rake up; it not only releases one from the task of genuinely understanding, but develops an undifferentiated kind of intelligibility, for which nothing is closed off any longer. (SuZ 169/BaT 213)” Doen alsof je een expert bent op een bepaald gebied terwijl je geen idee hebt waar je over spreekt – dat is veel kwalijker dan je op de vlakte houden. Natuurlijk is het onmogelijk om een lijn te trekken die aangeeft wanneer je genoeg over een onderwerp weet om je over een onderwerp uit te mogen spreken (I am not a Heidegger-pundit…), maar belangrijk is dat je in elk geval probeert waar je over spreekt te doorgronden.

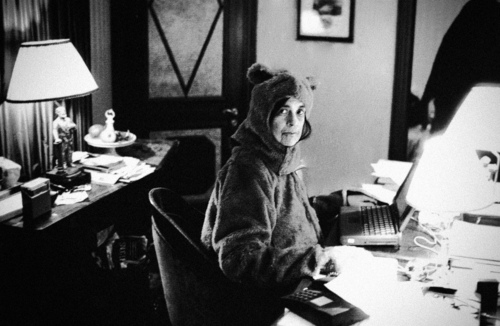

Bij dit alles weet ik een heel leuk Susan Sontag-filmpje, en ik ga jullie niet sparen (ook leuk om het filmpje helemaal te kijken):

http://youtu.be/7Mmi03G5oV0?t=5m6s

* Het hele essay kun je hier lezen (of in de bundel Both Flesh and Not). Geen idee of dat legaal is, maar veel plezier.

** Het is DFW week op tirade.nu, zie ook Anne-Marieke Samson afgelopen woensdag.